A NASA spacecraft's epic Pluto encounter is officially underway.

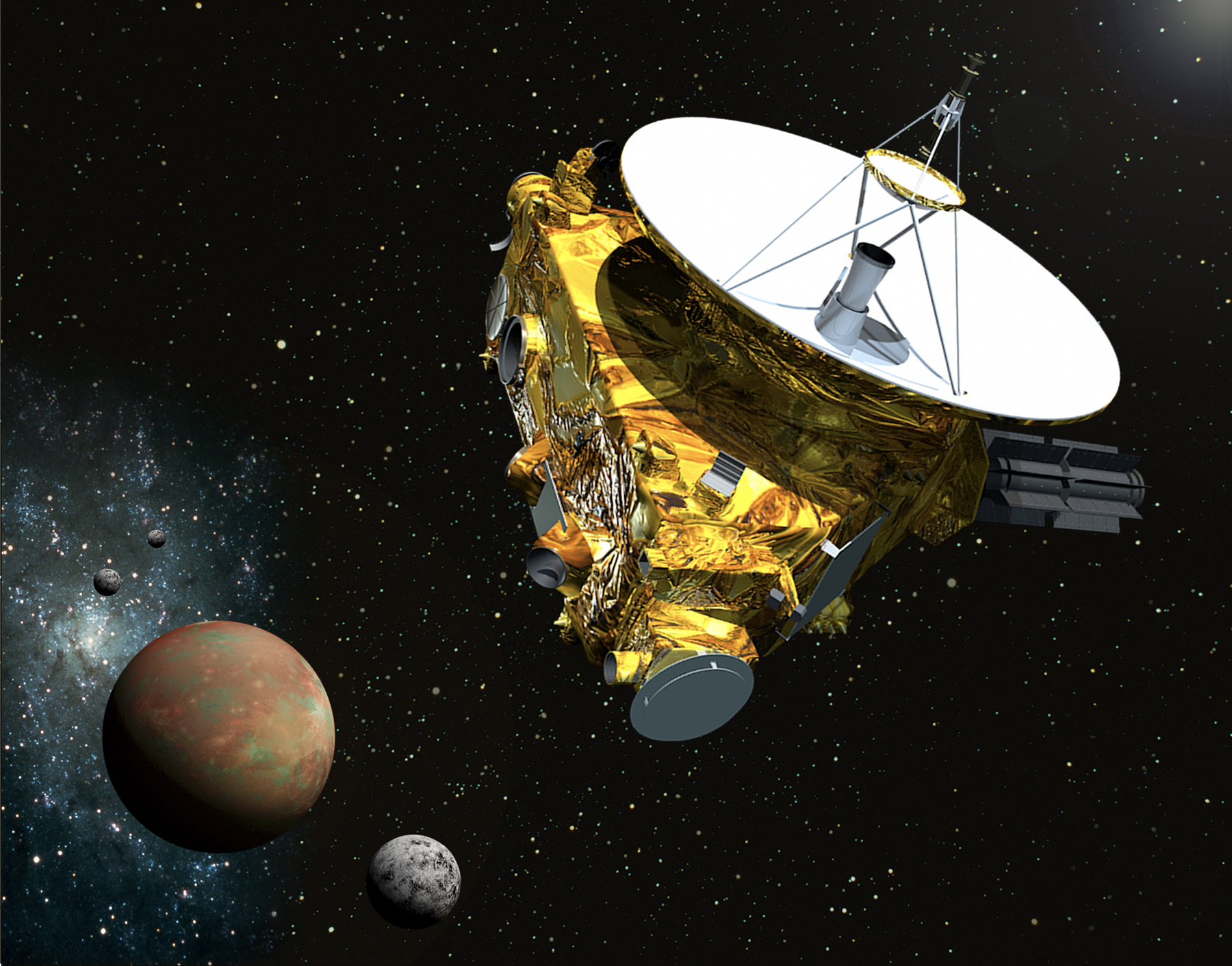

NASA's New Horizons probe today (Jan. 15) began its six-month approach to Pluto, which will culminate with the first-ever close flyby of the dwarf planet on July 14.

"We really are on Pluto's doorstep," New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern said last month during a news conference at the annual fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) in San Francisco. [Photos from NASA's New Horizons Pluto Probe]

A long journey

The $700 million New Horizons mission blasted off in January 2006 with the aim of lifting the veil on Pluto. The dwarf planet has remained a mystery since its 1930 discovery because it's so small and so far away. (On average, Pluto orbits about 40 times farther from the sun than Earth does.)

The piano-size spacecraft rocketed away from Earth at more than 36,000 mph (58,000 km/h), faster than any other probe. It has now covered about 3 billion miles (4.8 billion kilometers) during its nine-year journey through deep space.

"In a very real sense, this is the Everest of planetary exploration," Stern said of New Horizons. "This mission represents the closing of the first era of planetary reconnaissance. We've made it to the farthest place, with the fastest spacecraft ever launched."

New Horizons will use seven different science instruments to study Pluto and its five known moons. The mission's chief objectives include mapping the surface composition and temperature of Pluto and its largest moon, Charon; characterizing the atmosphere of Pluto and the geology of Pluto and Charon; and hunting for rings and additional satellites in the Pluto system.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In the 1990s, researchers began to realize that Pluto is not a lonely misfit; rather, it's just one of many dwarf planets and other icy denizens of the far-flung Kuiper Belt, which lies beyond Neptune's orbit. So New Horizons' observations should help researchers better understand an entire class of solar system bodies, mission team members said.

"We are going to the archetypal Kuiper Belt planet," New Horizons co-investigator William McKinnon, of Washington University in St. Louis, said at the AGU news briefing. "This mission will revolutionize our understanding of how the planets in the Kuiper Belt work."

Small, icy worlds like Pluto are probably the most common type of planet in the entire universe, McKinnon added.

The long encounter begins

Though New Horizons remains about 134 million miles (216 million km) from Pluto, it has already begun taking the dwarf planet's measure: The science-observation campaign officially began today, marking the start of "Approach Phase 1."

Many of the images New Horizons gathers during this phase will be used to keep the spacecraft on target toward Pluto, with the first course-correction maneuver, if necessary, possibly occurring as early as March. But some of the photos will be taken for scientific purposes, Stern said, and New Horizons will also characterize the Kuiper Belt environment using two different plasma sensors and a dust-counting instrument.

The pace of scientific activity will really start picking up in April, Stern added. And by mid-May, New Horizons will be close enough to snap the best-ever images of Pluto. (The sharpest photos of the dwarf planet to date were taken by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope; they show Pluto as a blur of pixels.)

It will only get more exciting from there. The most jaw-dropping images will be captured on and around July 14, when New Horizons zooms within about 6,000 miles (9,656 kilometers) of Pluto's surface.

The closest-approach pictures will not all be available right away, however. As a result of budget constraints, New Horizons does not have an articulated high-gain antenna, meaning the spacecraft must orient itself toward Earth to beam data home.

But New Horizons will of course be peering intently at Pluto during and immediately after the flyby. While some images will come down to mission control during this time, high-volume transmission of closest-approach data likely won't begin until early August, Stern said, and will continue for more than a year.

"From a scientific standpoint, this is going to look a lot like an orbiter [mission]," he said. "The spacecraft is long gone from Pluto, but new data is raining down every week, and every month, for 16 months."

The Pluto flyby may not end New Horizons' scientific work in the dark depths of the outer solar system: Stern and his team want to send the probe on to observe another Kuiper Belt object, and they've already identified two good candidates. If NASA funds this extended mission, New Horizons would reach its second and final target in 2019.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.